Dr Rachel Winchcombe

Lecturer in Early Modern History, School of Arts Languages and Cultures exchange fellowship at the Huntington.

In the summer of 2023, I was lucky enough to spend a month at the Huntington Library in California as a short-term fellow. The purpose of my trip was to uncover the answers to research questions that I had first proposed during my Leverhulme Early Career Fellowship: how did food management shape interactions between colonists, Indigenous communities, and enslaved people? How did changes to customary diets and environments impact early American communities? And to what extent do distinctive historical environments shape various affective relationships and identities? I had already begun thinking about these questions in relation to seventeenth-century Virginia and New England, drawing on the rich collections of the JRRI including early modern travel narratives, medical treatises, and printed herbals, but I wanted to extend my analysis to the Anglo-Caribbean context.

The Caribbean, as well as being home to a distinct climate and environment that shaped colonial food choices in different ways to those seen in continental North America, produced a unique set of colonial relationships in which access to food was key. Given the focus on producing the cash crop of sugar, the Caribbean colonies were dependent on food supplies from England and from other Anglo-American colonies. They were also reliant on the labour of enslaved people. By examining manuscript records of colonial governance in the Caribbean, my research at the Huntington will allow me to begin to recover the foodways of enslaved people from West Africa, highlighting how food cultivation and consumption could simultaneously be instruments of colonial resistance and repression, tools of cultural autonomy and suppression, and sources of comfort and misery.

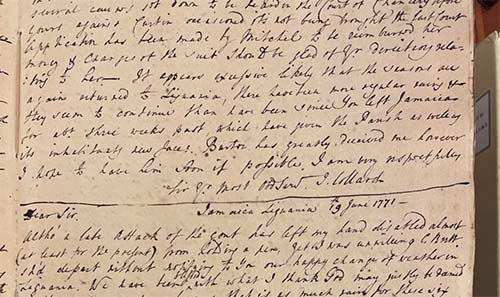

For example, the Stowe Papers, housed at the Huntington, and incorporating a range of manuscript documents relating to the day-to-day running of the Hope Plantation in Jamaica, reveal the often staggering disconnect between enslavers experiences of food consumption on the island and those endured by the enslaved. While plantation owners wrote about the delights of eating sweetmeats and pineapples produced in Jamaica, overseers and plantation physicians recounted the devastating ill health that enslaved people suffered due to scant food provisions. And yet these same records also offer glimpses of quotidian, albeit limited, forms of African resistance – enslaved people petitioned overseers for better provisions, ran away in an attempt to escape the brutality of life at the Hope Plantation, and used their indispensable labour as a strategy to negotiate for better conditions.

In the coming months, I hope to use this research, alongside research of printed accounts of the Caribbean colonies and material from the colonial records housed at the National Archives in Kew, to examine more fully the ways in which enslaved people used access to food and the cultivation of food as a form of resistance and cultural resilience, and conversely how English enslavers used food as a tool of control and oppression.