Royal Women, Cultural Exchanges, and Rus’ Ecumenical Marriages, circa 1000-1250

Talia Zajac, Leverhulme Early Career Fellow

This project investigates the roles of royal women as political actors, as Christian patrons, and as diplomatic ‘bridge builders’ between Byzantine Orthodoxy and Latin Christianity (modern Roman Catholicism) in the eleventh to thirteenth centuries. Despite accepting Orthodox Christianity from Byzantium in 988/989, the ruling clan of Rus’ (comprising present-day Belarus’, Russia, and Ukraine) concluded the majority of its marriages alliances with western Christian dynasties, including with the rulers of France, Anglo-Saxon England, Germany, Scandinavia, Poland, Bohemia, and Hungary.

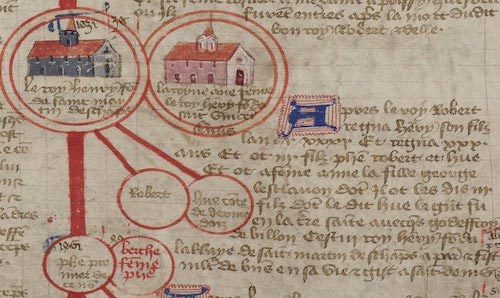

Sent to marry at foreign courts, dynastic brides in these marriage alliances brought with them books, material objects, and cultural practices from their homelands, helping to enable cross-cultural exchanges across Europe. Anna Yaroslavna (d. after 1075/79), for instance, became the wife of King Henry I of France in 1051, and, after Henry’s death in 1060, ruled with her brother-in-law as co-regent for her son Philip I (d. 1108). It was likely Anna who was responsible for introducing the Greek name ‘Philip’ into the Capetian dynasty of France. Gertruda of Poland (d. 1107/8), a Catholic bride who married the Rus’ Prince Iziaslav Yaroslavich (d. 1078), commissioned a personal prayer-book that combined Latin texts with Byzantine-style illustrations and Slavonic titles. The cases of Anna and Gertruda highlight the cultural and religious exchanges that could result from the ecumenical marriages of the Rus’.

At the same time, the many marriages concluded between the Rus’ and western Christian dynasties occurred as Christian ritual, church law, and theology began to diverge into what is now Orthodoxy and Catholicism. By looking at twelve case studies of royal brides in ecumenical marriages in the eleventh to thirteenth centuries, the project seeks to nuance the linear narrative of this divergence, commonly called the Church Schism. It will examine royal women’s lived experience of these emerging religious differences and will investigate their roles in keeping channels of communication open between these two Christian confessions.

The project thus aims to provide a new perspective on medieval European courts as sites of Orthodox-Latin Christian religious-cultural exchanges in which Rus’ women were active as queens, duchesses, regents, and patrons, while Latin Christian brides were likewise present as consorts and patrons in Rus’. Studying Rus’ ecumenical marriages therefore will contribute to a greater understanding of a) medieval women’s political agency b) gendered experiences of emerging religious differences and c) women’s contribution in enabling cross-cultural exchanges.